Local History

"From Dairy Valley to Cerritos" chronicles the development of a highly successful agricultural community into an ideal city.

"Cerritos Our History" features interviews with community members sharing their recollections of Dairy Valley and the development of the City of Cerritos.

The Natural History of Cerritos

A Changing City with a New Name: the 1960s

Forging Ahead through the 1970s

Focusing on Service: the 1990s and 2000s

Introduction

Cerritos was incorporated on April 24, 1956 as the City of Dairy Valley, a pastoral community of dairy farms, cows and chickens, dirt roads and sugar beet fields. People were few, with more than 100,000 cows outnumbering the humans by nearly 30 to one.

But the community pride and progressive thinking that have become Cerritos trademarks were evident nonetheless. Within a few short years, citizens acknowledged that rising land values and property taxes had made dairy farming uneconomical. During a special election on March 2, 1965, voters agreed to open up the dairy fields to new homes, laying the foundation for the diverse, thriving and beautiful community we enjoy today. A name change followed soon after, when a city contest produced the name “Cerritos,” a nod to the original Spanish land grant that was a prominent part of the region’s history.

With gracious new homes under construction citywide, Cerritos soon became the fastest growing community in California and city leaders saw the need to carefully guide our city’s growth. The first Cerritos General Plan, adopted on October 27, 1971, laid out a vision for a park-like community with acres of green open space, beautiful neighborhoods, services and shops close to homes, and a smart mix of commercial and industrial development.

That vision has certainly become reality, and our city’s unique personality, strengths, dreams and successes have come to fruition. Today, Cerritos is a close-knit community of diverse and active residents, world-class facilities, top-notch public services, financial security and beautiful vistas

The Natural History of Cerritos

Climate

Cerritos is located on a 275-mile-long strip of coastal land that runs from Santa Barbara to San Diego. Bordered on the east and north by mountains, the entire strip enjoys a Mediterranean climate, with warm to hot summers, mild winters and occasional rain.

Within the Los Angeles basin, Cerritos has a very unique climate called “semi-marine.” In this particular zone, the fog that often covers local beaches rarely reaches our city limits, but a cooling breeze nearly always makes its way up the San Gabriel River channel. This phenomenon helps protect Cerritos from the stifling heat and smog neighboring cities bear each summer, as well as the Santa Ana winds that menace the cities closer to the mountains. This nearly perfect environment has remained an attraction -- for the region’s earliest settlers, later for dairies and farmers and today for the 52,000 residents who call Cerritos home.

First Settlers

Anthropologists agree that Native American Indians were our area’s first settlers, arriving as hunters in search of prey. As more and more set up camp with their families, the Native Americans formed into villages of 50 to 100 people. All totaled, scientists believe that up to 700,000 Native Americans lived in California before European settlers arrived, with the groups speaking 22 separate languages and more than 200 dialects.

The Native Americans who lived in the Cerritos area called themselves Tongva (People of the Earth). Later, the Tongva would be named “Gabrielenos” after the mission that they built, San Gabriel Mission Arcángel.

The Gabrielenos were the largest group of Southern California Indians, with a reputation for being the wealthiest and most highly developed. The area that the Gabrielenos occupied as their home is now Los Angeles and the surrounding areas, from the San Fernando Valley to San Bernardino, along the coast from Huntington Beach to Long Beach, as well as the islands of Catalina and San Nicholas. The men would travel between islands and the mainland in plank boats called ti’at. Early records show that the Gabrielenos lived in simple reed and willow homes called ki’ish, with an opening at the top to let smoke out. Both men and women wore their hair long, and most went bare skinned or cloaked themselves in rabbit fur or deer skin for warmth.

The Gabrielenos lived off the land, deriving food from the animals or plants that could be gathered, snared or hunted, and grinding acorns as a staple. They wove intricate baskets and fashioned vital utensils and tools from wood, shells, bone and soap-stone. Local herbs were used for medicine, food and dye for their baskets. The Gabrielenos also bartered with other local villages, perhaps trading skins and acorns for pottery or other necessities. When their work was done, Gabrieleno families invented many kinds of games, loved to bathe, sang songs and told stories.

While no Native American village sites have been found within Cerritos city limits, many have been found nearby, including Tibahangna and Puvunga in Long Beach.

The Community's Early Origins

Early Explorers

The lives of the Gabrielinos and the entire future of the region took a turn beginning in the late 1400s, when European explorers set sail to America. Through the 16th and 17th centuries, a string of swashbucklers made their way to the West Coast hoping to establish colonies, develop money-making industries and, later, to set up elaborate commercial trade routes to Asia.

The country of Spain was among the first to gain a strong foothold in our region. With his eye on the entire West Coast, in 1765 King Carlos III sent one of his best advisors, José de Gálvez, who first took charge in Mexico, then moved up the uncharted frontiers to the north and west, starting new towns with donated funds and volunteer troops.

The California Missions

Hoping to secure the most desirable areas, Gálvez recruited a Franciscan priest named Father Junípero Serra to develop missions, with the central goal of “civilizing” the Native Americans and converting them to Christianity. A military force led by Captain Gaspar de Portolá guarded the missions and ensured the Native Americans’ cooperation.

On July 16, 1769, Mission San Diego de Alcalá was founded as the first of a chain of 21 missions to be established along the California coast. As the Serra-Portolá expedition blazed a trail up north, Father Juan Crespí, who accompanied them as chaplain, described in his diary “a very spacious valley, well grown with cottonwoods and sycamores, among which ran a beautiful river from the north-northwest… It has good land for planting all kinds of grain and such. It has all the requisites for a large settlement.” This proved to be one of the earliest descriptions of the Los Angeles Basin.

Establishment of the missions and “conversion” of the Native Americans was slow and grueling. It took years to build shelter and establish enough crops and cattle so that the settlements would be self-sufficient. Supplies came just once a year by ship from Mexico. The colonies were at first a drain on the Spanish economy and thought to be too fragile to survive, but to fend off encroachment by other European countries, Spain ordered the team to proceed. On September 8, 1771, Mission San Gabriel Arcangel was established as the fourth mission, and the one that would have the most direct influence over our region.

A new town, called el Pueblo de la Reina de los Angeles, was founded soon after in 1781 using craftsmen and experienced farmers from Mexico and, of course, Native American labor. Slowly the area began to prosper, with herds of cattle and sheep growing by the day, and fields, orchards and vineyards blossoming with the promise of crops. Barley and oats began to replace native grasses, and the entire Los Angeles Basin soon became covered with yellow mustard flowers grown from seeds the settlers had scattered.

Spanish Land Grant

The wilderness that is now Cerritos went first to the hands of a Spanish soldier. Three years after Mission San Gabriel was established, three men from Portolá’s first expedition approached the governor and asked permission to graze cattle on land near the mission. Their request was approved, with the stipulation that the land would continue to belong to the King of Spain. With this agreement, Corporal José María Verdugo accepted the very first Spanish land grant of about 35,000 acres on what is now Glendale and Burbank, and he named it Rancho San Rafael. A second grant was bestowed to Juan José Dominguez, who named his 75,000 acres Rancho San Pedro.

José Manuel Pèrez Nieto was granted the third and largest plot. Originally named La Zanja, and later Rancho Los Nietos, the grant covered 300,000 acres of what are today the cities of Cerritos, Long Beach, Lakewood, Downey, Norwalk, Santa Fe Springs, and part of Whittier, Huntington Beach, Buena Park and Garden Grove.

Records show that Nieto was a soldier who had accompanied the 1769 Serra-Portolá expedition as far as the new mission of Velicatá in Baja California. Nieto was stationed at the Monterey presidio in 1773 and at San Diego in 1777. The garrison roster at San Diego lists Nieto as a married soldier 34 years old, illiterate and Spanish. Nieto settled into a 20-foot-square adobe home, along with his wife, two children and his mother. As his family grew, a small community called Los Nietos grew around the original adobe. When he died in 1804 as the wealthiest man in California, Nieto bestowed the house to his widow and five children, with his eldest son Juan José acting as manager.

Life on the Ranchos

Life on the ranchos was hard, but conditions continued to improve. Soon after California fell under Mexican rule in 1822, full ownership of the ranchos was granted to the individuals who had first claimed them years earlier, including the Nieto family. New Mexican regulations encouraged overseas commerce, and trade soon flourished. The industrious ranchos began churning out much-desired cattle hides, beef tallow and other products for the rest of the world. The families now lived a comfortable life, hiring specialized servants and using their profits to buy clothing, furniture, food and tools from across the country. This marked the start of the great “pastoral” period of our region, with the nearby missions and pueblos thriving and the land covered with vineyards, fields, and hundreds of thousands of head of long-horned cattle.

In New Hands

Amid the arrival of a growing number of foreign settlers and the Mexican government’s new efforts to nationalize church property, Juan José Nieto’s children became concerned that others might lay claim to their land. In 1834, Nieto’s family asked for reconfirmation of ownership from the governor. The governor did confirm the land to Nieto’s heirs, but divided it into five ranchos.

Over the next 10 years, many of Nieto’s heirs sold their smaller ranchos to new owners, but, Juan José Nieto retained the largest plot. Called Rancho Los Coyotes, the land covered 48,825 acres that included the Coyote Hills, most of Coyote Creek and much of the land that would one day become Cerritos. Juan José built a gracious hilltop home on his property in 1831, near the location of the Los Coyote Country Club in Buena Park.

Juan José Nieto sold his plot to Juan Bautiste Leandry, a Sicilian-Italian shop owner from Los Angeles, who renamed the site Rancho La Buena Esperanza (“The Good Hope”). While Leandry died two years later, his wife, Francesca Uribe Leandry, remarried and lived there with her new husband, Francisco de Campo, for the next 20 years.

Through the 1830s and 1840s, cattle ranching remained the area’s main occupation. Native Americans continued to make up much of the labor force, and days were filled with rodeos, the branding of calves and the drying of cattle skins for trade. Cow hides were traded to New England merchants, with many shipped to the Boston area for conversion to leather goods. The best tallow was kept for making soap and candles on the ranchos, while the rest was shipped to the mines of Mexico and South America for use as candles. Much of the beef was left to rot, though the best was dried into beef jerky or given to the Native Americans who worked the ranches. Nearly everyone rode horses, and local residents became famous for their horsemanship. The ranchos also became renowned for their hospitality, hosting frequent celebrations and providing a comfortable stop for travelers on their way to Los Angeles. The Southern California cattle market boomed a second time from 1848 through the early 1850s, when newly rich gold miners from the north were willing to pay top dollar for beef.

Ranch Divisions

While local ranchers hoped this “grand fiesta” would never end, events of the 1850s soon put a damper on the celebration. Cattle ranchers in other states began to move their cows to the prosperous west, arriving with better quality animals. Miners and connoisseurs from San Francisco were no longer willing to pay top price for beef that now seemed stringy and tough. Soon the market for Southern California cattle disappeared and the ranchers who had become used to the finest things in life were instead mortgaging pieces of their property. Following scattered battles up and down the state, an 1848 treaty ended the Mexican-American war, and California was admitted as an American state on September 9, 1850. At the same time, hundreds of American pioneers who had arrived on the West Coast in search of gold now hoped to settle down on farms. Many moved on to the ranchos and became squatters.

While the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had assured local citizens of Mexican descent that their property would remain their own, in 1851 a federal land commission required the families to prove their ownership. In most cases, this was difficult. Business on the ranchos had been conducted very casually for decades, and few families held acceptable surveys or paperwork. Witnesses were allowed to testify to the ranchos’ boundaries, but it was difficult and expensive for most families to take their lawyers, translators and witnesses to San Francisco for the hearings. Over five years, more than 800 cases were tried involving more than 19 million acres. More than 500 claims were approved, 275 were rejected and the rest were withdrawn.

Because they had stashed away grant documents and a formal land survey, Francesca de Campo and Andres Pico won official ownership of Rancho Los Coyotes in 1855. Mrs. de Campo had inherited the land from her husband, while Pico was said to have loaned money, cattle or goods in exchange for half ownership.

This bounty had only lasted a few years when, in the late 1850s, Pico and de Campo experienced financial troubles and sold Rancho Los Coyotes to Abel Stearns, a Massachusetts native and seaman who arrived in Los Angeles seeking his fortune in 1829. After hauling cow hides for a few years, Stearns had set up a small store in Los Angeles where he invited local ranchers to trade their cow hides for other products. When trade ships arrived from the Northeast, Stearns would sell the hides for cash or more goods.

Slowly amassing a fortune, Stearns (at age 42) married Arcadia Bandini, the beautiful 14-year-old daughter of an important San Diego citizen, in 1841. The couple’s large adobe home on the plaza in Los Angeles, called “El Palacio,” soon became the social center of Southern California. Stearns became one of the richest and most respected citizens in the pueblo, serving in local government and later as a state assemblyman. By 1860, he had acquired all but two of the original Nieto ranchos, including the land that is now Cerritos, with property from San Bernardino to the Mexican border.

As the fortunes of the ranchos rose and fell, so did the fortune of Abel Stearns. Severe floods in 1861 and 1862, including two solid weeks of rain, changed the course of rivers and washed away many of the original adobe homes of the “golden days.” The floods were followed by the worst drought ever seen in Southern California. Thousands of cattle died and hordes of crickets devoured anything left that was green. Smallpox devastated the region and property values in the “cow counties” plummeted.

Delinquent in taxes, Abel Stearns nearly lost all of his property in 1868, before an old friend named Alfred Robinson convinced a group of San Francisco investors to form a land-sale company called the Robinson Trust, otherwise known as the Los Angeles and San Bernardino Land Company. The syndicate saved Stearns from bankruptcy, giving him $50,000 to settle his debts plus one-eighth of the profits. The team began a marketing campaign to entice buyers from the eastern United States and Europe, as well as soldiers returning from the Civil War. New rail lines and the California Immigration Union encouraged the new settlers. The Robinson Trust sold more than 20,000 acres in its first year, but Abel Stearns wouldn’t live to see his second fortune. He died of a sudden illness in 1871 while on a trip to San Francisco.

Cranford Airport

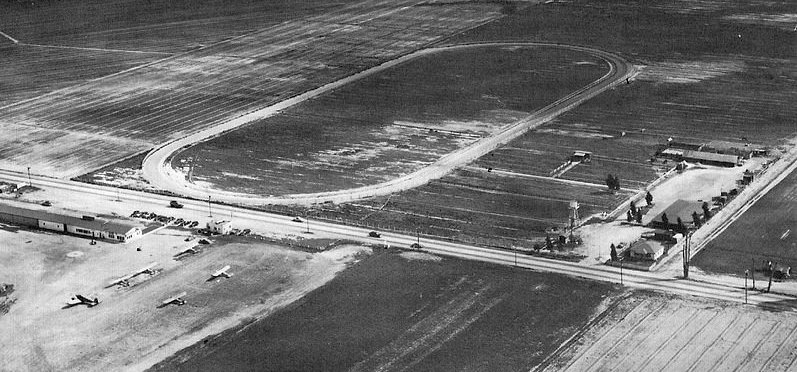

Cranford Airport, a small general aviation airport, was once located northwest of what is now the intersection of South Street and Carmenita Road. According to “Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields,” a website that is supported by the American Aviation Historical Society, the airport was operational from approximately 1945 to 1953.

A circa 1940s aerial view depicts the south end of Cranford Airport and shows six light single-engine planes parked next to a small building, with an oval racetrack across the street. The photo is from the “Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields” website and was provided courtesy of Dick Morris.

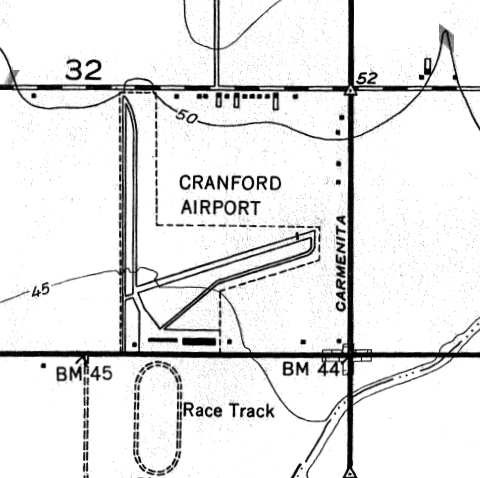

The 1949 United States Geological Survey map depicted Cranford as consisting of two 2,300-foot runways, one oriented north-south and the other northeast-southwest. Each runway had a parallel taxiway, and a ramp along the south side of the field had two buildings. The map is from the “Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields” website and was provided courtesy of Francis Blake.

The March 15 1947 issue of “The Ninety-Nines News Letter,” published by the Ninety-Nines International Organization of Women Pilots, noted: “There will be a flight to Bakersfield on April 12 and 13 for the Sectional social meeting. Shorty afterword, on April 26, members and guests will gather at Cranford Airport near Artesia for a bit of hangar flying and hopping. Clair McMillen, who instructs at Cranford, is now free of her back cast and will be on hand.”

The May 15, 1947 issue of “The Ninety-Nines News Letter” reported: “The month’s second meeting was for lunch and business at Cranford Airport, east of Artesia. It proved to be almost a “treasure hunt”, due to the difficulty experienced by some in finding the place – the surrounding territory being dotted with small unmarked towns accompanied by small unmarked airports. Cranford Airport, once it was located, turned out to be a nice place with generous runways, lots of hangars, a new and inviting office and lounge, and a spic and span cafe where substantial snacks could be had. Claire and Betty McMillen made the arrangements, Betty coming down from Bishop for the meeting. She said the Bishop airport was fixing up some nice little places to stay should the girls be flying up.”

An article titled “Civil Air Patrol Squadron Forms,” published in the “Los Angeles Times” on November 28, 1948, also mentions Cranford Airport. The story states: “Advancement of aviation in this area was noted today with the formation of the Artesia Squadron of the Civil Air Patrol at Cranford Airport under the direction of Group Cmdr. H.C. Livermore. As soon as the squadron is fully organized, it will undertake the recruiting of youths between the ages of 15 and 20 and form them into cadet squadrons. The adult group will sponsor the cadets and offer them preflight training.”

The “Los Angeles Times” reported on July 9, 1950 that “More than 200 youngsters vied against each other and a stiff breeze at Cranford Airport, Artesia yesterday for honors in the outdoor flight events at the Southern California Model Plane Meet. There were gliders, rubber-band powered craft a hundred whining gasoline-engined entries that zinged around like so many super-mosquitoes.”

A City Takes Root

Just a few decades later, no marketing was necessary to draw new settlers to the Los Angeles Basin. With its perfect climate and growing towns, Southern California had become a destination for adventurous families seeking a new life “out West.” More than 100,000 people lived in the city of Los Angeles in 1900, with several other thousands in outlying communities that were surrounded by farms.

A man named Henry E. Huntington helped this growth by devising a new system of rail lines to connect the growing burgs. He launched construction of his Pacific Electric Railway in 1902, and within just a few years the very first “Red Cars” were carrying passengers from Los Angeles to the new town of Long Beach. As the rail system grew, farmers realized they could leave their fields and commute to better paying jobs in the cities. With convenient transportation as a draw, the local population boomed. In the space of a decade, the city of Long Beach alone grew from 2,200 people to more than 18,000 residents.

At the same time, the town of Artesia was flourishing. The community had been established in 1875 with the opening the Artesia Schoolhouse on the corner of 183rd Street and Alburtis Avenue. The area’s free-flowing Artesian wells, which had given the town its name, had created a successful farm region, rich with grapes, sugar beets, other vegetables and fruits, ferns and flowers, poultry and dairy farms.

By the turn of the 20th century, smaller towns were eager to gain the prestige, convenience and economic benefits of becoming a Red Car stop, so in 1906, when the line was extended to Santa Ana, leaders of Artesia worked steadily to convince Pacific Electric to build through their town. A new station was built on Artesia’s Main Street (what is today Pioneer Boulevard), with a small green park across the street for waiting passengers. Artesia’s business district soon flourished, with shops and offices clustered between today’s 186th Street and the Pacific Electric Station. An old schoolhouse was sold and moved in 1910 to a new site on Pioneer Boulevard where Postma’s Furniture Store is located today. The school house became a general store with a hotel upstairs, while a new brick Artesia Grammar School was built nearby. The next stop to the east was a new town called Waterville, which was eventually renamed Cypress.

Thanks in part to the Red Cars, the Los Angeles area continued to grow through the early 1900s, with the city of Los Angeles doubling its population every 10 years. Outlying communities such as Artesia also continued to grow, as new local industries continued to demand more and more workers. Many people commuted daily across the basin by railway or car, and Artesia became a successful “bedroom community” of 4,000 residents.

Farming Overtakes Ranching

By this time, most of the long-horn cattle that had roamed the area the previous century had made way for crops, and farms sprawled across the land. The well-known Gorinis Family farm, along South Street between Bloomfield and Shoemaker Avenues, produced acre upon acre of daffodils, dahlias and other flowers. Other local farmers raised a variety of corn known as Orange County Prolific, which would grow to 14 feet tall. The variety produced a few edible ears, but was most valuable for the long, thick stalk and leaves that made excellent food for livestock. The Pacific Electric hauled tons of sugar beets, sweet potatoes and other goods from Artesia to stops throughout the Southland.

The area was also home to several vineyards, and George Frampton and O.J. Thompson ran a successful winery near the intersection of Pioneer and Artesia boulevards. Small local dairies cropped up, supplying milk to the Harvey Smith cheese factory in Norwalk and the Lily Condensed Milk company in Buena Park.

With the local agricultural market booming, farm irrigation soon depleted the area’s natural Artesian wells, which had once been free-flowing. Most farmers now found it necessary to look below ground for the water they needed, and it is said that the sound of water pumps could be heard across the fields every morning. Families that couldn’t afford pumps would have their children take turns at hand-pumping until their water tanks were full.

Small Town Life

Along with tending the fields and walking along dirt roads to school, life in the area was typical of small town America. Thelma Ryan, who later married the future president and became First Lady Patricia Nixon, spent many years in Artesia and Dairy Valley as one of the many children who enjoyed all the area had to offer. As Julie Nixon Eisenhower wrote in her mother’s biography, young Thelma would often accompany her parents on buggy trips to downtown Artesia, which consisted of a bank, a barbershop, two blacksmiths, a hardware store, Scott and Frampton’s general store and the Niemes’ drugstore.

Children from local farms would attend Artesia Grammar School, and later ride a bus to Norwalk High School before Excelsior High School was built in 1925. On hot days after school, the children would gather near today’s Carmenita Road and South Street for a dip in the reservoir at Anthony ranch, which spread 100 feet across and 16 feet deep. Other childhood exploits weren’t quite as wholesome. As Mrs. Nixon recalled, one Halloween night, “goblins” relocated a wagon to the roof of the Pacific Electric station, and moved outhouses to the roofs of the buildings along Pioneer Boulevard – a story that has become legendary.

Mother Nature

Mother Nature would regularly play a little mischief of her own, dousing the area with winter storms. Before today’s modern storm channels, low lying Norwalk, Bellflower and Artesia were especially known for flooding. Most winters, the area near Gridley Road, between Del Amo Boulevard and South Street, became a lake, and Coyote Creek regularly overflowed and flooded what is now Hawaiian Gardens.

After a severely wet winter in 1916, even one of the largest local rivers, the San Gabriel, overflowed. Life on the farms came to a halt, with crops inundated with water and the dirt roads an impassable mess. The Pacific Electric Red Cars, however, were able to remain in operation on their raised tracks, shuttling people and goods through even the worst weather. But despite its convenience, the rail line soon earned a few enemies. The Red Cars’ raised tracks, it turned out, worked as a dam, regularly trapping the flood waters. On this particularly stormy night, a rising tide soon threatened the businesses along Pioneer Boulevard. As legend holds, a mysterious figure saved the town by blasting a piece of the track between Pioneer and Studebaker Roads with dynamite. The water level quickly subsided.

Such explosive tactics were no longer needed by the 1930s, when large dams and reservoirs were built in the San Gabriel Mountains to capture dangerous runoff. “Spreading dams” were soon after built to control the floods and allow some of the winter downpours to soak into the ground and replenish local wells. By the end of the 1960s, all of the local rivers and creeks had been lined in concrete, speeding the delivery of water to the ocean and away from neighboring properties.

Earthquakes, however, remained an uncontrollable force, and on March 10, 1933, Artesia residents were reminded of Mother Nature’s power. Late in the afternoon, a 6.3 magnitude quake struck the nearby Newport-Inglewood fault. Had the earthquake occurred just a few years earlier, when most of the region was devoted to ranching, the damage may have been negligible. But the population was now booming, with Long Beach and its neighboring towns filled with homes, businesses and other structures. Nearly no consideration was given to earthquakes in those days, and most structures had been built using techniques common in the quake-free Midwest.

When the late afternoon temblor hit, the unreinforced brick-and-mortar buildings that dotted the landscape simply fell apart, killing more than 102 residents and causing more than $40 million in damage. Long Beach was devastated and there was serious damage to buildings in Torrance, Garden Grove and Compton. Several buildings in Artesia and Norwalk were so damaged they had to be torn down. Twenty-two local school buildings were destroyed, including Excelsior High School, which had been built just six years earlier at Pioneer and Alondra boulevards. Once a showcase for the community, Excelsior lost its decorative portico and sustained other major damage. Artesia Grammar School was so badly damaged, it was replaced by another building on the same site, called Pioneer School.

Fortunately, students and faculty had all gone home before the late afternoon earthquake hit, a blessing that may have prevented hundreds of deaths and injuries. The state legislature acted immediately to pass the Field Act, which called for a strict new building code. All new schools, the act stated, must comply with a state building code and be carefully supervised.

Dairies

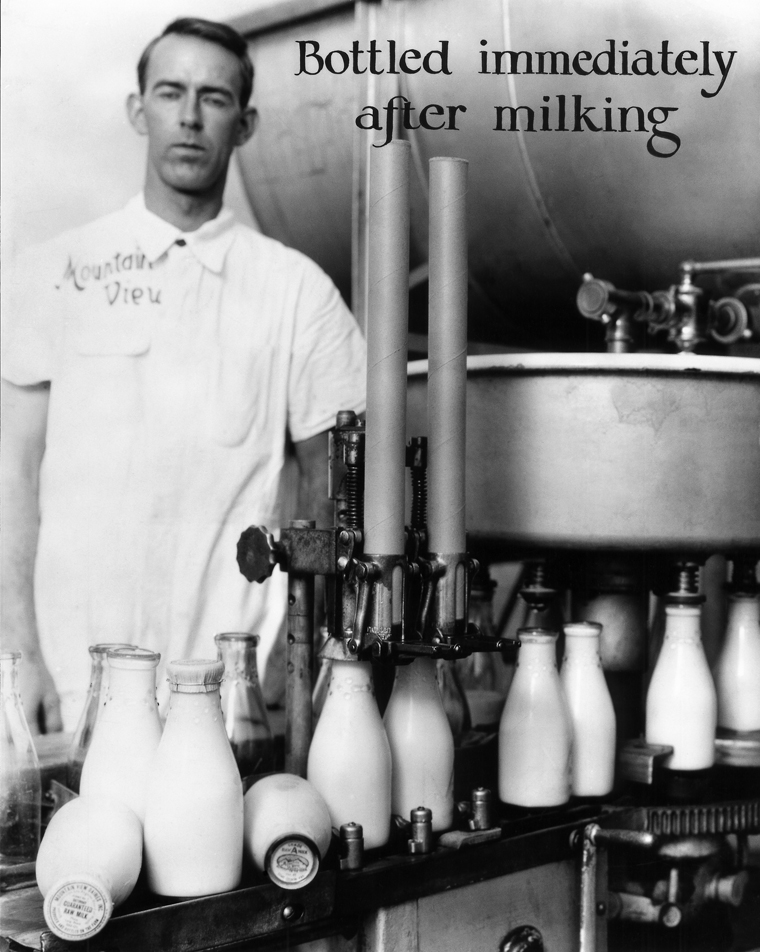

A local dairyman in a crisp white uniform oversees the production line at Mountain View Dairies, Inc. As the bottle lids boasted, the “guaranteed raw milk” was “produced and bottled on the farm.”

A Dairy Valley farmer leads his herd down a dirt road on a sunny Southern California day. Hay (shown on the right) and feed were also big commodities in the area, while manure was prized as fertilizer.

This pastoral scene shows a typical Dairy Valley farm operation, with hundreds of black-and-white Holsteins housed in corrals. Cows would be milked by hand twice a day. Pictured is the future site of the Cerritos Towne Center.

But floods and earthquakes would never be enough to overshadow the beauty of the Cerritos area, and its near-perfect climate and convenient location continued to attract new residents and entrepreneurs. It was directly after the Long Beach earthquake, in fact, that a stream of Dutch and Portuguese immigrants began to build Artesia into one of the nation’s largest dairy capitals.

Over more than a century, hundreds of thousands of cows had roamed the land that is now Cerritos. But on the ranchos of the early 1800s, cows were typically prized only for their hides, meat and tallow – not for their milk. Milking a long-horn cow on the ranchos was done only when necessary to obtain milk for an invalid or an infant. After all, as the story has been passed down, it was a three-man job to lasso the cow and try to hold it still long enough to extract a container full of milk.

Dairy farming became more desirable in the 1850s, when American settlers moved to California with their taste for fresh milk, butter and cheese. As the demand for dairy products grew, dairy farms sprung up first near San Francisco and later in Southern California. By the 1880s, there were several cheese factories and creameries in the Los Angeles Basin, with small local dairies supplying the milk. Most were concentrated on a belt from Compton through Buena Park.

The local dairy industry continued to grow through the 1920s, as did the need for milkers. With the promise of jobs, dozens of Portuguese immigrants who had worked at dairies in the San Joaquin Valley moved south to Los Angeles County. As the Los Angeles metropolitan area was filled in with housing, offices, shops and industry, many dairies moved east, cementing the Artesia area as a dairy capital. The following decade, in the 1930s, hundreds of Dutch people --descended from generations of dairy farmers -- were lured first to the Midwest and then to Southern California. They brought with them to Artesia the hands-on skills and expertise the dairy industry demanded.

Local dairies were, in short, milk factories. Gone were the rolling grassy pastures; instead, cows were farmed on small plots, averaging 10 acres or less with about 100 cows. The animals were now fed scientifically regulated fodder that included hay, cottonseed meal, copra and other exotic food. Each cow was expected to produce her quota of 1,200 gallons of milk a year, or a new cow would take her place. Fertilizer was a side business for many farmers, and local suppliers that sold hay and other dairy feed turned millions of dollars in profits.

Dairying, by all accounts, was hard work and there was little room for sentimentality. The cows had to be kept healthy and fed, and milked regularly. Equipment had to be perfectly sterile. The cows worked seven days a week, 52 weeks each year, and the dairymen kept the same schedule. But the hard work paid off: the area’s semi-marine climate was perfect for the cows and made possible phenomenal milk production. Some of the area’s cows, in fact, produced 3,000 gallons of milk a year – twice the national average. All totaled, the local dairy industry produced half a million gallons of milk monthly by the 1940s, for an annual profit of $61 million.

The Portuguese dairy workers, many of whom originated in the Azores islands, left an indelible mark on the region that continues to this day. The group established a warm community in the town of Artesia, with a fellowship hall forming the community’s social center. It was here that the Portuguese-Americans were able to retain their language, culture and family ties. Meanwhile, the Dutch farmers created a “Little Holland” in the area, from Paramount to west Buena Park. Here, they could hear sermons in the Dutch Reformed churches, read newspapers from their native land, and enjoy a rich social and cultural life in their native language. When Queen Juliana and Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands toured the United States in 1952, they made a special visit to this area.

The Founding of Dairy Valley

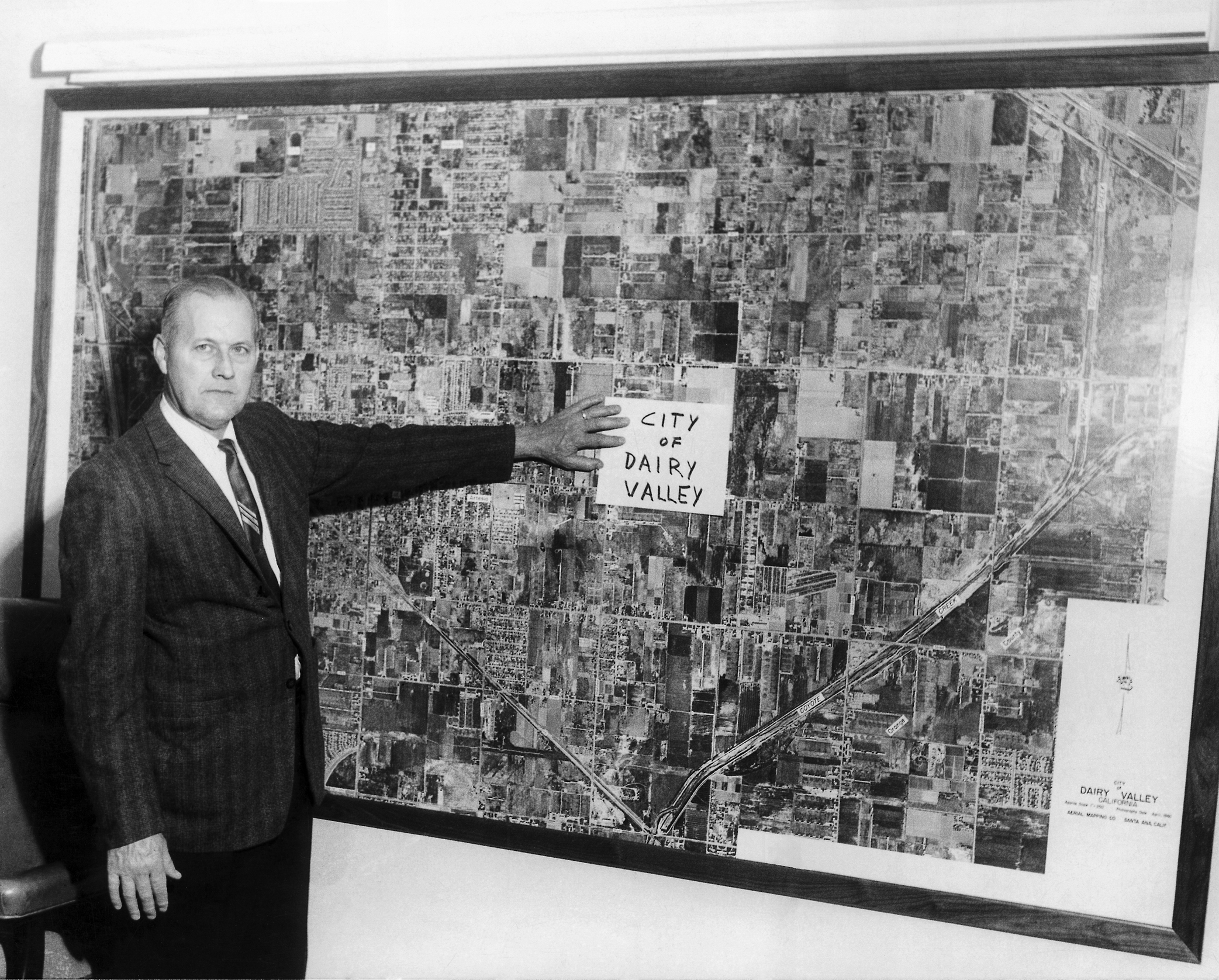

Fred Troost, who served as mayor and councilmember on the Dairy Valley/Cerritos City Council in the 1960s, poses by one of the first aerial photos of the fledgling city.

Milk made for a serious and profitable business for Dairy Valley’s farmers. Cows were the vital part of the “assembly line,” as shown in this photo taken in September 1959.

The Building Boom

By the 1940s, there was something in the air in Dairy Valley beyond the mooing of cows. The Los Angeles County housing boom had begun with a chorus of hammers, saws and backhoes.

World War II had made Southern California an important industrial center, with thousands of workers moving to the area for good jobs in the local factories, shipyards and plants that supplied the military. One of the area’s major employers was the Douglas Aircraft Company, which opened on the eve of World War II in 1941 next to Daugherty Field in Long Beach. During the war, the facility produced more than 31,000 aircraft for the U.S. Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps, including bombers, cargo transport and reconnaissance planes. The facility later went on to produce commercial jetliners. After the war, many of the local workers stayed, and thousands of returning veterans joined them on the assembly lines.

To accommodate this growing workforce, developers sped up production of dozens of tracts of homes in Long Beach, Artesia and Norwalk. The most spectacular example was Lakewood, where a single developer bought 3,375 acres of farmland and, just as the last crops were being harvested, laid out 133 miles of paved streets. More than 10,000 homes were built in the first two years alone, using the most modern construction techniques. Power diggers trenched foundations in just under 15 minutes, carpenters used automatic nailing machines and pre-cut lumber, and conveyor belts carried shingles to the roofs. Priced at $7,000, the homes were snapped up by buyers who often took advantage of G.I. loans guaranteed by the Federal Housing Authority.

As Lakewood grew to the west, Norwalk settled in to the north and Buena Park burgeoned to the east, Dairy Valley’s farmers could see their area’s rural roots start to wither.

Cities Rise from the Fields

As they took shape, neighboring cities also began to assert their independence. Throughout Southern California’s rural past, most towns were recognized simply because they had a post office, school district, train station or chamber of commerce. The county took care of street maintenance, police and other services. But as local cities evolved from fields to suburbs, many took action to “incorporate,” to meet the state’s legal requirements for an independent city government.

In many cases, this led to land scuffles. When Lakewood’s population exploded in the 1950s, for instance, this “instant city” became home to 77,000 people. While many assumed Lakewood would be annexed by its big-city neighbor, Long Beach, Lakewood leaders disagreed. They made arrangements to contract with Los Angeles County for many of the services that would normally put a new city into debt, including police and fire protection, libraries and street maintenance. With this smart financial move, Lakewood incorporated in 1954.

Other cities took notice. In fact, so many local leaders were interested in the “Lakewood Plan” that the county set up an office to provide technical assistance. The state legislature also helped these growing burgs by passing the Bradley-Burns Act in 1956, which provided a one percent sales tax revenue for cities. With this financial assistance and the spirit of independence, 47 new cities were incorporated in the Los Angeles-Orange County area from 1954 to 1974.

A Push from Artesia

One of these cities was Artesia. By August 1951, Los Angeles County Ordinance 5800 had established the “Artesia Zoned District” south of Alondra Boulevard and between the San Gabriel River and Coyote Creek to the point where the two streams meet. With help from Lakewood attorney Angelo Iacoboni, who had spearheaded his city’s incorporation drive, the Artesia Chamber of Commerce embarked on a campaign in 1955 to incorporate the Artesia Zoned District and create one of the largest and wealthiest cities in Los Angeles County. The chamber staged an informal meeting at Mike’s Café on Carson Boulevard in August to discuss the idea, inviting local dairymen Jim Albers, Frank Leal, Leslie Nottingham and Albert Veldhuizen.

It was soon apparent, however, that this was not a “preliminary” meeting. Boundary papers and petitions were ready for distribution, calling for development that would not include poultry ranches or feed lots for cattle. Housing developments, the papers stated, would be sandwiched between the dairies.

The dairymen quickly got the message: cows wouldn’t be welcome. Not only would the feed-lot ban place a burden on their dairy operations, there was no doubt the new homeowners would object to the dairies’ odor and flies, as they had in neighboring cities. The plan not only threatened the dairymen’s way of life, but also the multi-million dollar businesses they planned to pass on to their children.

Our Founding Fathers Meet

The very next day, the dairymen met with fellow Farm Bureau members at the Central Milk Producers Association offices on Pioneer Boulevard. Several pledged money to pay for an attorney, and paperwork was drawn up that would set the stage for incorporation of a separate, agriculturally based community, carved from the Artesia Zoned District, that would be named Dairy Valley.

There were similar stirrings just over Coyote Creek, where an area that would someday be known as La Palma incorporated itself as Dairyland to escape annexation by Buena Park. The city of Cypress, originally called Watertown, also incorporated as Dairy City in 1956 to make clear its agricultural focus.

But the love of farming wasn’t the only thing driving Dairy Valley’s early leaders; they were also very astute entrepreneurs. As campaign literature would later state, the men were an average of 47 years old, and had been successful local businessmen for 25 years. Their combined operations included 235 acres of valuable land, 3,200 dairy cows and 20,000 chickens, and they tended to live in large, well-built homes, spending vacations in Europe. Most were on local, county and state agricultural boards and served as trustees for their schools and churches. They were savvy in management and knew that if the area was correctly developed, it could only enhance their investments. When the dairies were ready to relocate, the men, of course, hoped to realize the greatest profit from their land.

Albert Veldhuizen, a Minnesota native of Dutch descent who lived with his wife and four sons on a Studebaker Road dairy, was elected chairman of the Dairy Valley committee. Other active members and future city council candidates included John Schoneveld from Iowa; Jacob “Jim” Albers and Louis Struikman, both born in Holland; Jack R. Bettencourt, originally from Massachusetts; and A.C. Pinhiero and Francisco C. De Mello, natives of the Portuguese Azores. Representing the poultry farmers were George Sperou, who was also an engineer, and Hal Rees, who had a career recording music for motion pictures before he established a poultry ranch with 15,000 birds.

Cerritos Begins

Dairy Valley’s incorporation was brought before voters in 1956, and the campaign was truly contentious. The dairymen worried that the Artesia boosters would prevail, with their four-to-one advantage among voters. The dairymen also feared that central Artesia, with an assessed value of $4 million, would hold power over the dairy area, valued at more than $18 million. They predicted that property and school taxes would inevitably rise, a special blow to the dairymen whose children most often attended private church schools.

Nine dairymen joined the slate of candidates for Dairy Valley’s first city council, but they took the unheard of step of campaigning as a bloc, taking out a full-page ad in the “Artesia News” to show their commitment to a common vision. “This is not a conventional political platform,” they wrote. “These are the sincere pledges and guarantees of each and all of us.” Promoting their idea for a new agricultural city, the dairymen promised not to “freeze things as they are now,” but to encourage commercial development, clean industry and one house per five acres. They promised a simple and economical government, with just two employees and no salary or expense accounts for the councilmen. What’s more, the men promised lower county taxes and no city property taxes. As in Lakewood, the county would be contracted to provide services.

“There are only two choices for this area,” their ad declared. “Do nothing on April 10th and within a year find yourself a forgotten, heavily taxed minority in someone else’s town; or vote ‘yes’ on April 10th and take intelligent advantage of this first and last chance to have truly economical self-government here.”

The men first sketched out a city that would include Artesia, Hawaiian Gardens and a strip known as Monterey Acres, now part of Lakewood. But by election time, city boundaries had been scaled back. Political shenanigans, however, had not, and the tension continued to build. In one now-legendary move, the dairymen even arranged to buy up a new housing tract known as Artesia Crest to move in their milkers. This savvy move ensured that the new homes would be filled with voters friendly to the dairymen’s cause.

The election was finally held on April 10, 1956. Although the results were close, 441 to 391, the dairy and poultry men prevailed. The Secretary of State approved the Articles of Incorporation and Dairy Valley officially became a city at exactly 9:16 a.m. on Tuesday, April 24, 1956. Resembling a horse-shoe encircling Artesia, the new City of Dairy Valley was home to 3,500 people, 32,000 cows, 83,000 chickens, 9,600 turkeys and 105 acres of row crops, including fields of strawberries and sugar beets as far as the eye could see. The city’s value was assessed at $26 million and the first city budget was pegged at $33,190.

A Brand New City: the 1950s

Shovels festively painted for the occasion mark the groundbreaking of Dairy Valley’s first City Hall on December 21, 1959.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Frank Bonelli was a featured speaker at Dairy Valley City Hall’s groundbreaking. The stage was set up next to the iconic row of palm trees that once lined Pioneer Boulevard.

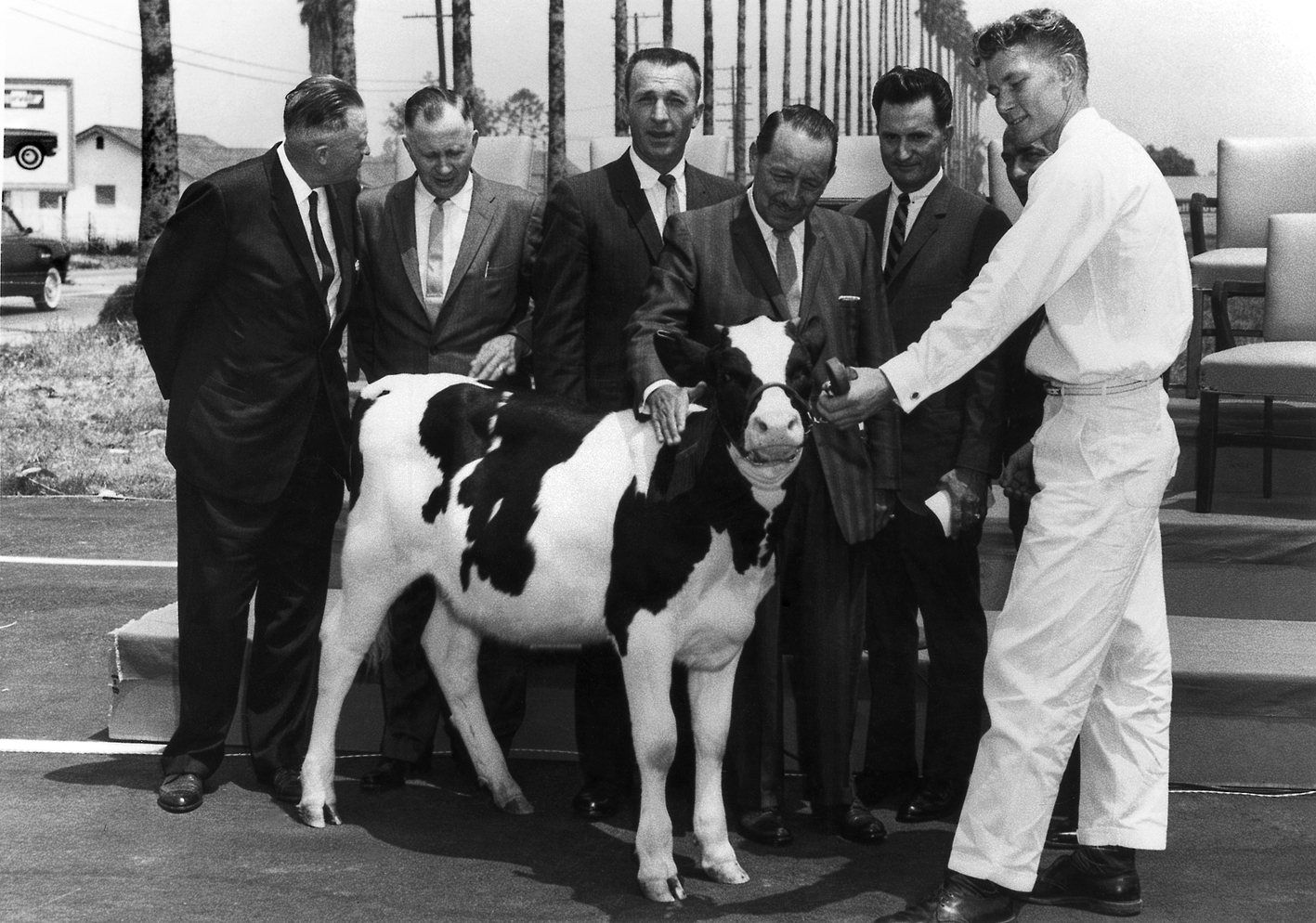

Los Angeles County Supervisor Frank Bonelli was later presented with a calf. He is pictured with Dairy Valley City Councilmembers (left to right) Louis Struikman, Jim Albers, Alex Moore, Joe Gonsalves, Frank Leal and an unidentified calf herder.

The City of Dairy Valley - 1956

During this momentous election, five men were chosen from the slate of nine candidates to serve as Dairy Valley’s first city council. Jacob Albers was a 16-year dairyman whose five children and 1,000 cows had the run of his 45-acre farm at 19510 Pioneer Boulevard. He had made a name for himself in the local farm and dairymen’s associations, as well as the Artesia Rotary Club and the Christian Home for the Aged. Jack R. Bettencourt was a Massachusetts native and 30-year dairyman, with a wife, six children and 175 cows on his 15-acre farm at 16926 Marquardt Ave. He had shown his leadership skills as a member of the Knights of Columbus and the local Farm Bureau. Hal Rees and his wife, a native of Catalina Island, had lived in the area for 46 years. A veteran of the motion picture industry, he now devoted his time to his poultry farm and the Farm Bureau, Rotary Club and Holy Family Church. The youngest member at 36, Albert Veldhuizen was the father of “four husky sons” and the owner of a 13-acre farm with 475 cows at 16330 Studebaker Road. He, too, was an active Rotarian and member of the Farm Bureau and Artesia Reformed Church. Louis Struikman, who had won over A.C. Pinhiero by just one vote, was a native of Holland who lived with his wife and son on a 30-acre farm with 700 cows at 13841 Artesia Boulevard. He was also a familiar face at his church and a long-time member of the local Milk Control Board.

The triumphant group wasted not a second, holding their first community meeting on election night at Carmenita School auditorium, the only room in town big enough to hold an audience. Bettencourt was elected Dairy Valley’s first mayor, and William “Bill” Cecil, business manager for Central Milk Sales at 17032 S. Pioneer Blvd., was named temporary city manager. Joy D. Horn was hired as city clerk and treasurer, for an annual salary of $350. Soon after, the new city council acquired a $3,000 loan from a local feed company to pay the new staff members and to set up a temporary city hall at the Central Milk Sales office. (City offices moved later that year to 11810 E. 186th St.)

One of the provisions of the April 10 election was that Dairy Valley would have a city manager form of government. With this structure, the citizens elect a city council to set policy, the mayor serves as chairperson, and a city manager is hired to prepare the budget, oversee daily operations and advise the council. When Bill Cecil returned to his old job at Central Milk Sales in September, the council quickly chose Mayrant D. “Mac” McKeown as Dairy Valley’s first permanent city manager. Just beginning his career at age 33, McKeown held degrees in public administration from Long Beach State College and the University of California at Los Angeles. He was assisted by Margaret Bengel, who had replaced Mrs. Horn as city clerk and treasurer, and later by Agnes Hickey, who became the official city clerk in April 1957 and remained in that position for 24 years.

Daily Operations

The newly minted leaders quietly went about the business of running their new city, considering development requests for new businesses and housing, instituting an annual “Fix Up, Clean Up” program, setting up a fertilizer cooperative and dispatching a safety team to inspect the city’s four private swimming pools. They put their stamp on a number of new laws banning illegal trash dumping, abandoned cars and calf-skinning operations that were the scourge of many rural areas. They launched the city’s recreation department, hiring John List to supervise the Carmenita School playground for $1.75 an hour.

Meanwhile, they enlisted the county’s help to pave Dairy Valley’s dirt roads. County engineers estimated it would take $3 million to transform Dairy Valley’s rustic thoroughfares into “civilized” condition, and work soon began to convert Pioneer Boulevard, South Street and Artesia Boulevard into modern, paved, two-lane roads. Most of the other streets were left unpaved.

Residents, meanwhile, had grown tired of the area’s notorious annual flooding. Many had been evacuated from their sodden homes by the Coast Guard during the heavy storms of January 1952, and memories were still fresh. After any heavy rains, most residents assumed Gridley Road would be a lake. Local dairymen sometimes aggravated the problem by erecting levees around their own corrals, forcing flood waters onto their neighbors, who were growing weary of these tactics. The situation improved considerably by 1957 when a much needed drainage ditch was built from 183rd to South Street and later extended to Coyote Creek. The San Gabriel River and Coyote Creek were tamed a few years later when the Army Corps of Engineers lined them with concrete.

Neighborly Disagreements

McKeown and the council also faced their share of manmade challenges, including ongoing tussles with neighboring cities over land. In their 1956 campaign advertising, the council candidates had pledged, “We are not figuring on joining the scramble to annex new land. If folks with a common interest adjoining Dairy Valley want to come in, they will be welcome, but you won’t find us out grabbing new areas!”

But this easy going attitude soon took a back seat to pride and finances, and the council worked hard to preserve the land they felt was rightfully Dairy Valley’s. Lakewood and Bellflower, for instance, had expected to annex the dairies west of the San Gabriel River, while Santa Fe Springs and Norwalk hoped to expand their industrial areas southward. After several court battles, Dairy Valley gained acreage and the city’s western boundary was set at Palo Verde Street. In one case, however, the city council wasn’t so reluctant to give up land. When non-dairy residents of Artesia Crest, near Pioneer and Del Amo, organized a movement to recall the city council, the dairymen managed to keep their seats and the tract was swiftly annexed to Lakewood.

At the same time, Dairy Valley’s city council battled with trustees of Cerritos College, who had set their sights on the corner of Alondra Boulevard and Studebaker Road, farm land they judged to be safe from flooding. Dairy Valley’s leaders, however, felt the development would set a precedent that would threaten their rural zoning. The college would also grow and demand more dairy land, they predicted, and it would attract staff and students who would require housing. The matter was settled out of court when property was ceded to the city of Norwalk and an eight-foot-high, 1,200-foot-long wall was built to mark the boundary. (At the same time, Dairy Valley’s city council easily passed a request by Bellflower Christian School to build Valley Christian High School on Artesia Boulevard.) Today, while Cerritos College has a Norwalk address, much of the campus is situated in Cerritos,

After many adjustments, in 1957 the city of Dairy Valley was finally settled at 8.9 square miles. With dairies relocating to this new agricultural center, the city soon boasted 400 dairies with over 100,000 cows, producing more than $80 million in milk products each year.

A Charter City with an Official City Hall

Dairy Valley continued to evolve into the 1960s, with voters opting to switch from a “general law” city to a “charter” city in November 1958, gaining broader powers and local zoning control. City Manager McKeown, meanwhile, earned a pay raise from $400 to $850 a month, plus accolades for a string of accomplishments. He managed to secure Dairy Valley’s annexation of the area’s only car dealership, S & J Chevrolet, as well as Olin Krum’s Pioneer Mills, Barr Lumber, Jack Stansbury Dairy Supplies and other prime businesses near Pioneer Boulevard and South Street. Sales tax, state funds and even billboard rentals helped boost the city’s coffers.

Dairy Valley’s neighbor, Artesia, incorporated in 1959 with 1.62 square miles and 10,000 residents. Cerritos College opened that July, providing a central junior college campus for classes that were once held at night at local high schools. The Santa Ana (5) Freeway opened to motorists, near the city’s northern boundary, and Dairy Valley’s great expanses invited creative ideas for development. At one time, Dairy Valley was suggested as the site for the Dodgers’ new baseball stadium and as a perfect location for a small plane airport. Alas, the Los Angeles Airport Commission disagreed.

The community did agree, however, on the need for an official city hall, and on June 11, 1960, city officials celebrated the opening of a modern structure of green stucco and decorative blocks at 19400 Pioneer Blvd. Designed by an architect friend of McKeown’s, sketched free-of-charge over a spaghetti dinner, the building housed offices for city staff and a council meeting room that seated up to 70 people. The building was landscaped with a small lawn and stately palm trees. At the same time, on McKeown’s advice, Dairy Valley pulled out of the county library district to save $20,000 a year. But on learning that the city was required by the state to provide library services, McKeown brought a shelf full of books from home, setting up Dairy Valley’s first “public library.”

To boost revenue, the city began charging a range of business license fees, from $5 a year for cow and chicken farms up to $100 annually -- plus 10 cents per barrel -- from an oil company they hoped would strike “gold” north of 166th Street. The Producers’ Livestock Marketing Association relocated from Los Angeles to the corner of South Street and Carmenita Road, and a fee-per-head on animal sales gave a much needed boost to the city’s purse. Meanwhile, a 10-cents-per-head tax on hog sales helped ward off loud, smelly hog farms, but the fee attracted national attention and a lawsuit from the hog farmers’ association. (The council later agreed to change the tax.) McKeown was lured away to Paramount with an offer of $20,000 per year, and William Stark took his place.

National Attention

By now, Dairy Valley’s successful experiment in agricultural zoning had become a local marvel, attracting even national attention. Feature articles were published in the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, California Farmer, the U.S. government’s Yearbook of Agriculture for 1963, and even a newspaper in Montreal, Canada. The story of Dairy Valley would later be featured in a U.S. Department of Agriculture publication, and became a staple in textbooks on urban planning read by college students across the country.

A Changing City with a New Name: the 1960s

This 1960s era aerial photo looking east shows Bloomfield Avenue in the foreground and 183rd Street to the right, with the new 91 Freeway cutting across the landscape and subdivisions slowly filling in the cow pastures to the east.

Model cows flank a cake baked for the City of Dairy Valley’s 8th anniversary in 1964. Pictured from left are Councilmember Louis Struikman and his wife, Alice, Mrs. Lois Leal, Mayor Pro Tem Alex Moore, Mayor Frank Leal, Councilmember Fred Troost, Mrs. Kenneth Penrose of Artesia and Councilmember J.N. Albers.

In this June 1964 photo, carpenter Bill Crawford works on the framing of Dairy Valley’s new Richard Gahr High School at 11111 Artesia Blvd. between Studebaker and Gridley roads.

California Governor Ronald Reagan (left) meets with Cerritos representatives in Sacramento on March 2, 1967, recognizing the city’s name change. Pictured with Reagan (left to right) are Cerritos City Councilmembers Frank Leal, Tony Cordeiro, Jim Albers, Mayor Fred Troost, Senator George Deukmejian and Assemblyman Joe Gonsalves.

Mayor Fred Troost (left) and Councilmember Louis Struikman (far right) congratulate Mr. and Mrs. Marvin Chenevert and their five children as they move into the very first tract home in Dairy Valley in 1966.

The City of Cerritos officially makes its debut to motorists with the installation of new freeway signs. While the elevation hasn’t changed (64), the population undoubtedly has.

Start of an Exodus

This new “agricultural city” was clearly a success. But as much as Dairy Valley’s first leaders wanted to preserve the city’s rural roots, time marched on, and soon so did the cows. With many of the area’s original dairymen retiring or relocating to Chino or California’s Central Valley, by 1962 Dairy Valley’s dairies had been reduced by nearly half – to 240 – with 53,000 cows producing 217,000 gallons of milk a day. Construction was now underway on two freeways – Interstate 605 and State Route 91 – that would cut across the city, displacing 32 dairies and the fertilizer cooperative, but making the area more desirable for commuting homeowners.

As milk production slowed and thousands of new homes took shape in spotless new suburbs throughout the county, Dairy Valley residents turned their gaze toward “greener pastures.” During a special election in July 1963, proponents of a citywide zoning change suggested that it was “Time to Cash In” on rising land prices, encouraging the city’s dairies to move elsewhere to make room for suburban development.

The ads were certainly enticing. One memorable full-page piece in the “Artesia Advocate” showed dramatic “then” and “now” illustrations of the city. “Then” showed a hand gripping a fistful of dirt, while the picture opposite showed a well-dressed family gazing at a futuristic city of homes, industry, bullet trains, skyscrapers – even a rocket ship. “Today, your Dairy Valley property can be profitably sold or highly-developed,” the ad read, “if it is properly re-zoned!” The ad went on to warn of poor widows who would be forced to sell their husbands’ fields for half to one-third their potential value. Housing authorities and real estate professionals agreed that pricing for acreage was peaking, the ad also warned, so much so that the average home price could rise to “$25,000 MINIMUM. How many families of any age group can afford a house of this cost? This can cause the building of homes to be reduced dramatically,” the ad warned, “causing over-inflated land prices to collapse.”

But voters didn’t respond well to these dire warnings. Despite any financial opportunities, residents weren’t yet ready to bid farewell to their community’s bovine past, and the measure was soundly defeated.

Residents were receptive, however, to minor zoning changes that promised a boost to the city treasury. It had become increasingly expensive to oversee Dairy Valley’s progress, and the city budget had topped $260,000 by 1963. Leaders hoped that new retail centers and a light manufacturing area along the city’s major thoroughfares would help bring not only services, but also sales tax and business license revenue to the city. To help bring this idea to fruition, the Dairy Valley Chamber of Commerce was founded on July 2, 1963, and John Corcoran was hired full-time to attract new businesses to town. The city’s very first shopping center opened soon after at the corner of Pioneer and Del Amo boulevards, featuring an Alpha Beta grocery store, TG&Y variety store and several smaller shops.

Increasingly proud of their new city, Dairy Valley residents held tightly to their borders. In one case, Dairy Valley leaders quashed an idea set forth by neighboring Artesia, which hoped to annex Hawaiian Gardens, a little town south of Dairy Valley which had gotten its name from a popular soft drink stand that once stood at the corner of Carson and Norwalk boulevards. Artesia and Hawaiian Gardens could only be connected if Dairy Valley allowed a corridor to be cut through the bottom of its “horseshoe.” The plan was rejected, and Hawaiian Gardens later incorporated on its own in 1964 with just under a half square mile of land.

A Master Plan

In cases like these, Dairy Valley’s residents held on tenaciously to their land, their ideals and their pastoral way of life throughout the early 1960s. But as neighboring cities continued to grow around them, it became clear that development in Dairy Valley was inevitable. What was needed, they decided, was a plan. If the city was destined to grow, leaders and residents alike wanted to ensure that its valuable dairy fields were put to the best possible use.

The city hired experts Louis Turrini and Kenneth Outwater from Robert H. Grant and Company to prepare its first Master Plan in October 1964, which described Dairy Valley as “the last large unurbanized region in the metropolitan area.” At the same time, to make Dairy Valley more desirable for future development, the city took out $3 million in municipal bonds to pay for a new water system that included modern 20- and 24-inch lines and, later, a seven-million-gallon reservoir at the corner of Marquardt Avenue and 166th Street. The system was later christened when Mayor Jim Albers smashed a quart of milk across one of the freshly laid concrete pipes.

These upgrades were finished just in time. By the following year, in 1965, a county reappraisal had doubled Dairy Valley’s property taxes, making the city a very expensive place to operate a dairy. Once again, the idea of changing Dairy Valley’s zoning was presented to the city’s voters. This time, the majority supported a change, with a vote of 440 to 324. Dairy Valley’s zoning was officially redesignated from agricultural to residential.

Housing developers wasted no time. Shortly after the election, paperwork was filed at City Hall requesting permission to build 1,000 new homes. The first tract to open, called Stardust Homes, offered beautiful abodes priced from a modest $24,000 to $30,000 to entice sturdy, middle-class buyers. To mark the momentous grand opening, Mayor Fred Troost presented a black-and-white cow statue to Mr. And Mrs. Marvin Chenevert, who, with their five children, were the very first residents to move into a Dairy Valley subdivision, at 19203 Crossdale Ave.

Planning for an “Explosion”

Following the Chenevert Family’s lead, new homebuyers began arriving in droves, bringing with them great hopes for the future, pride in their new community, and rows of fresh-faced children trailing behind them. Dairy Valley’s leaders quickly decided that the community’s growing families needed a better place to play than in the streets. Richard Bigler Associates was hired to prepare a comprehensive, long-range plan for parks and recreation. The document mapped out a solid plan for providing neighborhood parks citywide, with a range of carefully chosen amenities – from baseball fields to playgrounds to shady picnic grounds. The plan also called on the city to use every financing program available to purchase vacant land for future parks. With this plan in place, through the next decades, Dairy Valley boasted the highest number of parks per capita of any city in the area.

At the same time, while generations of Dairy Valley children had been served for nearly a century by their local schools, it soon became apparent that the community needed one central school district to oversee its educational direction. In 1965, the three smaller districts were combined into one, and the Artesia district (founded in 1875), Bloomfield district (founded in 1885) and Carmenita district (founded in 1902) merged to become the ABC Unified School District. That year, Carver Elementary, Tetzlaff Junior High and Gahr High School were completed. In addition, the district drew up plans that called for 28 elementary schools, six junior high schools and three high schools to meet the needs of what they expected to be a population explosion.

Our First General Plan

While school district officials planned for new campuses, Dairy Valley’s city staff continued to map out the best possible uses for the community’s dairy fields. Stanley A. Morgan was hired as assistant to the city manager and William Stookey, an MIT and Caltech graduate who had worked on the city’s $3 million water main, was hired as the city’s chief engineer. Local Assemblyman Joe Gonsalves, who had himself grown up in Dairy Valley and served on the city council, secured a $33,000 state grant to prepare Dairy Valley’s first General Plan.

California State Law requires every city to adopt a General Plan to provide a framework for the long-term physical development of the community. But for Dairy Valley, as for many other cities, the General Plan was much more than just a legal document. It served as a vision for the community’s future, a firm statement of its character and a tangible plan for preserving and promoting the city’s heritage, values and objectives.

City leaders professed that they didn’t want Dairy Valley to be like so many other new communities that had mushroomed without direction. They wanted to attract solid, middle-class homeowners. They wanted all of the utility lines to be buried, with no poles and lines to mar the city’s skyline. They wanted an abundance of parks, big community centers and smaller neighborhood playgrounds within walking distance of every family. And they wanted a variety of commercial centers and an unobtrusive industrial center tucked away from residential neighborhoods.

When it was finalized in 1971, the comprehensive General Plan laid out a vision for a beautiful city with a balanced economy that would provide a safe, attractive home for growing families. Nearly half of the city’s land was allocated for residential development, another 18 percent was dedicated to commercial, industrial and professional uses, and the remaining third was designated for schools, parks, flood control facilities, utilities, public streets and government buildings. More importantly, the General Plan called for a progressive city with deep respect for the environment, and a lush, park-like setting that would give the community a unique beauty. Through the following years, city council members Dennis G. Bradshaw, Frank D. Lee, Barry A. Rabbitt, James S. Reddick and Robert J. Witt were instrumental in overseeing the city’s change from dairy land to a beautifully planned community.

Today, the Cerritos General Plan is much more complex, addressing land use, circulation, housing, conservation, open space, noise and safety. But since its adoption in 1971, the document has been revised just twice, in 1988 and 2003, building on the accomplishments of the past, addressing the challenges of the future, and preserving the city’s enduring values.

A New Name for a Modern City

While this planning was underway, Dairy Valley’s leaders also decided to face their future with a brand new name. This modern suburban community, of course, could no longer be called Dairy Valley. As neighboring Dairyland remade itself as “La Palma” and Dairy City transformed itself into “Cypress,” Dairy Valley’s Chamber of Commerce began pushing for a more contemporary name for their master-planned community.

The Chamber’s commercial and industrial committee set to work preparing a list of suggestions. “Los Coyotes” would have been a fitting tribute to the area’s first name, Chamber members felt, but the name didn’t quite have the sophisticated connotation they were looking for. Likewise, “Freeway City” was briefly considered, but it too lacked the “classy image” Chamber members and city leaders hoped for.

“Cerritos” was suggested as a name that would link the city with the successful junior college that was now becoming well-known throughout Southern California. Cerritos also conjured up romantic images of the old California rancho days, city leaders felt. Historical accuracy, however, it didn’t have. Rancho los Cerritos was actually the westernmost part of the old Nietos rancho, all of which was west of the San Gabriel River, with its eastern boundary at Bellflower Boulevard. Alas, none of the old Rancho los Cerritos even touched Dairy Valley. What’s more, Abel Stearns had originally spelled the name “Sierritos,” meaning “little hills,” in a survey map in 1834 -- but what hills he was referring to remains a mystery. Voters didn’t seem to care about these technicalities. “Cerritos” was the resounding winner during a city election on January 10, 1967.

Growing Better with Age

Just a little over a decade after the city was first incorporated, Cerritos had become a different place entirely. The acres of feedlots, strawberries and chicken farms had begun to make way for suburban neighborhoods. By April 1968, 31 new tracts were either completed or underway, with more than 2,000 new homes dotting the landscape. Huge construction crews were putting the finishing touches on the 605 and 91 freeways, crossing Cerritos in each direction and giving the city a convenient, central locale between Los Angeles and Orange counties. Enormous drainage, water and sewer projects were underway, some connecting with systems in Norwalk, La Palma and Lakewood. First Lady Patricia Nixon attended the groundbreaking in 1969 of a little park located on the farm where she had lived as a child. The family house later became a museum and recreation center.

The first section of the Artesia (91) freeway was dedicated in June 1968, complete with a skit starring “Daisy, The Educated Cow,” who was trained by her owner, Mayor Pro Tem Tony Cordiero, to chew through the grand-opening ribbon. This appeared to be one of the last of the “cute cow” presentations. In the months to come, many of the area’s 90,000 cows were loaded onto trucks and shipped off to new pastures.

As the cows headed east into the horizon, starting an exodus that would last into the next decade, Cerritos was swept up in a spirit of pride and progress. A bumper sticker from the era said it all: “Cerritos – The Freeway City – A Prestige Address – The Geographic Center of Southern California.”

Forging Ahead through the 1970s

Taking the place of the strawberry fields at the corner of Bloomfield Avenue and 183rd Street, Cerritos Public Library was designed as a source of community pride, independent of the county library system.

City leaders eyed this vacant plot of land on 166th Street, next to a tract of newly built homes, as the perfect location for a large community park. City Park East (now Cerritos Park East) opened soon after in 1972.

The city selected the same architect who designed Cerritos Public Library, Maurice H. Fleishman, AIA, to create the new Cerritos City Hall. Here, the modern 52,000-square-foot, three-story structure begins to take shape in November 1976.

The remains of the old De Voss Dairy are removed from the land at 18600 Bloomfield Ave. in December 1975, making way for the 15-acre Heritage Park. The De Voss family home was preserved and converted to a community center.

The ambitious plans for Heritage Park called for a three-acre play island complete with a New England-style village. Watched over by the new church steeple, bulldozers clear the way for a surrounding lake in September 1976.

As with most of the city’s major developments, Cerritos Auto Square was once dairy land. This photo shows Studebaker Road in the foreground, between South and 183rd streets. To create the auto mall, the city purchased land from Jake Knevelbaard Dairy and seven other property owners.

Hoping to strike gold with the idea of a regional auto mall, Cerritos city leaders and representatives from five major auto dealers broke ground on the innovative project in 1980. The dignitaries are pictured at the future home of Browning Oldsmobile.

Homes, Sweet Homes

Thanks to the network of new and modern freeways, commuters were now zipping throughout Los Angeles and Orange counties in the 1970s and Cerritos truly was the geographic center of Southern California. And thanks to a scramble by developers eager to build homes on the area’s now-vacant cow pastures, Cerritos quickly became the building capital of Los Angeles County.

By 1971, exactly 3,367 building permits, valued at more than $90 million, were issued in Cerritos, representing 70 percent of the single family homes under construction in the county. Within the span of a few years, the city’s population also exploded, from a count of 4,373 residents in 1968 to 37,748 residents counted during a special census in 1972. The area’s assessed valuation boomed. While Dairy Valley’s land had been worth $28.5 million in 1958, property in the new city of Cerritos was worth well over $124 million by 1973.

Addressing the City’s “Blight”

Just as the dairy fields were slowly replaced by tidy, family homes, the dairymen on the city council were slowly replaced by engineers, salesmen, attorneys and environmentalists. For the first time in the early 1970s, there wasn’t a single dairyman on the council. It was at this time the city began investigating a practice that promised to transform its remaining cow fields: redevelopment.

In the late 1940s, after World War II, suburban development began drawing residents and shoppers outside America’s downtowns, leaving city centers – and often historic buildings – to deteriorate. To reverse this trend, the government passed legislation that would allow cities to replace slums and urban “blight” with prosperous new buildings. Cities could create “redevelopment agencies” to oversee improvements in specific “redevelopment zones.” Revenue for improvements was generated by freezing taxes in the area and issuing bonds for the cost of new developments that, over time, would attract tenants and bring revenue and growth. Redevelopment agencies had the power to condemn buildings, relocate tenants, buy and resell land, make plans and install streets and public facilities. Cities across the country used this process to rejuvenate entire neighborhoods and bring vital services to neglected areas.

While Cerritos didn’t have slums or crumbling buildings, city leaders saw “blight” in the pasture lands that covered the city’s west side. So on November 17, 1970, the Los Cerritos Redevelopment Agency was established, with authority over 820 acres bounded by the San Gabriel River on the west, Alondra Boulevard on the north, South Street on the south and Studebaker Road, Eric Avenue and Gridley Road on the east. With hopes for a prosperous future, the newly established Cerritos Redevelopment Agency (made up of the city council members) agreed to invest $30 million in the area, with visions for a large retail center and an innovative “auto mall.”

Within a few short years, their plan began to bear fruit, with the opening of Los Cerritos Center, a 100-acre shopping complex built at Gridley Road and South Street by developer Ernest W. Hahn, Inc. The first phase opened in 1971, and the second in 1972. At last, residents rejoiced that they were able to shop locally at four major department stores – Sears, Robinsons, Broadway and Orbachs – as well as150 smaller specialty stores. A large Fedco department store was sited across the street. The city council and “Miss Cerritos” remained busy attending grand opening ceremonies and cutting ribbons -- and at one time a long string of pearls -- to open the new stores.

One of the area’s first “shopping malls,” Los Cerritos Center was completely covered, air conditioned and impeccably maintained. More important, the center accomplished exactly what it was supposed to, bringing thousands of dollars of sales tax revenue to the city. In fact, retail sales in Cerritos grew tenfold in just four years, topping $207 million in 1974. With this success, a Los Angeles Times report on redevelopment named Cerritos a prime example of what could be done with excellent planning and investment. Soon after, on May 7, 1975, the city set aside another 1,615 acres on the east side of town, to be called the Los Coyotes Redevelopment Zone.

Development Discord

But this success in Cerritos still failed to impress voters in neighboring Artesia. Hoping to streamline efforts to provide facilities and services, the city councils from the two towns proposed a merger in the early 1970s. The issue certainly touched a nerve, drawing three-fourths of Artesia’s voters to the polls. The result: 1,140 “yes” votes and 1,362 “no” votes. With longstanding pride in their community, many Artesians balked at the idea of being absorbed by the young city next door. Others feared that their homes would be razed in favor of new development. Their fears were quelled by the resounding vote, and many of their homes stand today.

At the same time, local critters also fought to hold on to their territory. Housewives whose homes had been built near still vacant fields, were upset to find their backyards crawling with black widow spiders -- a reminder that Cerritos hadn’t been urban for very long. Local skunks, opossums and foxes also dug in their heels, seeing no reason to leave, while meadowlarks and pheasants called to each other across open fields.

While the new homes didn’t seem to affect the local wildlife, the city’s strict zoning rules did ruffle a few feathers. In one legendary squabble, city leaders had a philosophical clash with the Chamber of Commerce, after which the city cut off the chamber’s $850 subsidy and even took back the office furniture. Long-time Chamber leader John Corcoran resigned for another post.

Local merchants also protested the city’s strict sign ordinances, which received national attention when the city’s new Toys ‘R’ Us store was told the trademark “R” could not be reversed in their sign. After the uproar, the city council decided instead to reverse its opinion. Nevertheless, the star at Carl’s Jr. could not be on the roof, city leaders declared, and the Big Boy statue at Bob’s restaurant would have to stand demurely in the restaurant lobby. The Big Yellow House restaurant was instead painted a tasteful cream. The city no longer needed billboard revenue, so these large roadside signs quickly disappeared, as did any neon signs, flashing lights, banners or whirly-gigs that detracted from the city’s refined countenance.

After a few legal tests, the state Supreme Court upheld the city’s right to make zoning changes in local land use, and the county Superior Court gave its nod to the Cerritos sign ordinance. The rules still stand today.

Glorious Growth